Lebanon’s identity resides largely in the uniqueness of its geographical location and the diversity of its landscapes. From the thin coastal plain to the summits of Mount Lebanon, from the Bekaa plateau to the Anti-Lebanon mountain chain, this strong sequencing of landscapes is exceptional for such a small country. Its geography is part of the country’s fundamental wealth, one that should be the basis for rich territorial planning and sustainable local development.

Instead, this wealth is disregarded because of visionless development. Not only are master plans largely absent, but regulatory frameworks, when they do exist, are limited zoning plans that do little more than tell how much to build and where. In these documents, forests, agricultural lands, terrasses, shorelines, summits, valleys, and hillsides are not valued or recognized; they are indifferently slated as buildable land, under zones for residential, industrial, or touristic development. “The unbuilt” is viewed as voids to ultimately fill. Occasionally, the Lebanese authorities announce the creation of nature reserves to protect areas of high ecological importance. These reserves, however, cover limited parts of Lebanon’s rich environment and fail to address the complex challenges facing the country’s natural resources.

As a result, unregulated urban sprawl has disfigured much of the territory. Corruption, negligence, and lack of leadership have worsened this phenomenon and much has been lost in the process. Yet a lot remains that can still be preserved, provided an adequate regulatory framework is established with a political will driven by public interest. The region of Jabal el-Cheikh (Mount Hermon), is one such area.

A Region on Lebanon’s Borders

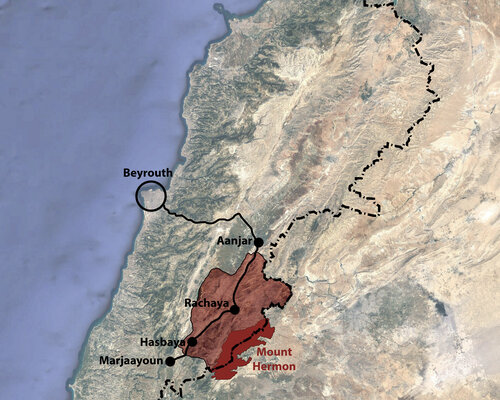

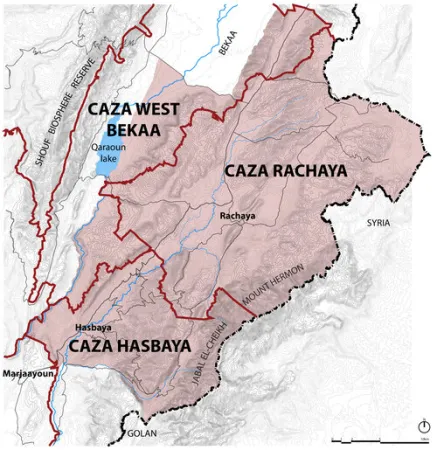

The region of Jabal el-Cheikh centers around Mount Hermon and spans across two districts, the Caza of Rachaya and that of Hasbaya, along Lebanon’s south-eastern border. Though the majority of Mount Hermon is situated on Lebanese territory, about half of its slopes are divided between Syria, the Occupied Golan, Occupied Palestine, and the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) buffer zone.

It is a 90km drive from Beirut, up and down Mount Lebanon and across the Bekaa. In an excessively centralized country such as Lebanon that tends to neglect regions far from the capital, it stands disconnected from the dynamism of Beirut. Furthermore, fenced by rows of hills, it is not a point of passage and stands relatively secluded. Its location along a highly sensitive border with conflicting countries also contributes to a form of marginalization – though the region has been peaceful since the retreat of the Israeli Army in 2000.

An Opportunity for Sustainable Development

Is it because of this multifactorial isolation and potential instability that the region of Jabal el-Cheikh did not undergo the urban development that occurred in most other Lebanese regions? Is it because of some particularly strong cultural identification to local landscapes, a closer relationship with land and agriculture, or demographic and socio-economic factors? Whatever the causes, the region of Jabal el-Cheikh has maintained the integrity of its natural environments, which have been mostly protected from chaotic urbanization, large-scale pollution, or quarrying activities. Its landscapes, exceptional in their diversity, also carry some of the richest cultural and archaeological heritage of the country.

Though the region also faces vulnerabilities that threaten its current state of conservation, it also offers a major opportunity to anticipate and act before major damage is inflicted upon it. It is thus pressing to establish adequate policies and protective measures that are necessary for its preservation and to implement them with proper public action before it’s too late. Jabal el-Cheikh has the potential to become a visionary precedent for sustainable regional development in Lebanon.

Description of the Area

- Toponymy and Boundaries

Mount Hermon stands out as a monolithic pyramidal shape that dominates the surrounding geography and whose summit (2,814m high) is the second highest in the Middle East. Its ominous volume certainly conjures a sense of sacredness, which is fittingly expressed in its name; “Hermon” is derived from the Semitic root “HRM”, which means “sacred place” or “place apart”. Jabal el-Cheikh (its Arabic name) is a reference to the snow that covers its summit during half of the year and that resembles the white skull caps of the religious Druze who inhabit the area. - Natural Landscapes and Biodiversity

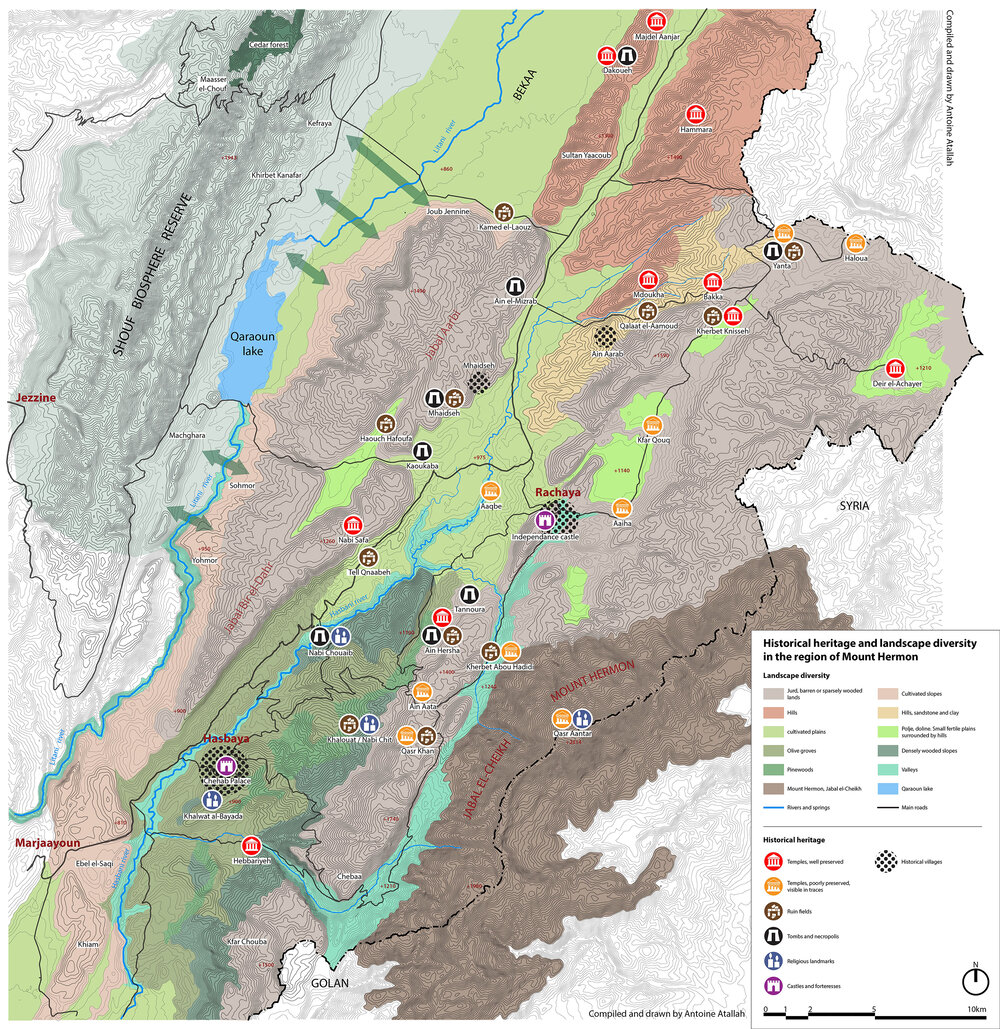

Mount Hermon’s sides are rugged with crevices, cliffs, and sinkholes, all eroded by the snows. Sparsely wooded, this “jurd”, (the colloquial name for barren highlands) however, hosts a variety of shrubs, bushes, grasses, and flowers. At the foot of the mountain, sceneries constantly shift, with diverse geologies and vegetations, much like the rest of Lebanon, which is known for its distinct ecosystems. The region’s unique landscapes includes arid hilltops and plateaus pegged with strangely shaped limestone outcrops called “dolomites”, cultivated plains, wooded slopes, terraced and planted hillsides, river valleys, and even “poljes” (rare fertile plains that become seasonal lakes in winter and spring).The diversity of landscapes within an area that’s around 600km² is exceptional and carries a biodiversity that is just as varied. Many endangered mammals find refuge in the region, including hyenas, boars, hyraxes, foxes, and wild cats. It is also a major passageway and resting space for migratory birds. Different varieties of oak trees, junipers, hawthorns, willows, poplars, pines, and wild fruit trees constitute the region’s diverse tree cover.The landscapes are also closely related to human agrarian and culinary practices. The profusion of wild plants and flowers generates a hive of beekeeping activity and allows for the widespread practice of foraging for medicinal plants and edible herbs. The many pastures cater for one of Lebanon’s largest populations of goats and sheep and generate an abundance of milk-based products. The olive oil produced around Hasbaya is said to be some of Lebanon’s best as well. - Historical Heritage

Located along ancient trade routes that run between the Bekaa, Palestine, and Syria, on lands rich in water and fertile soil, the region of Jabal el-Cheikh was inhabited across all periods of history. The ruins of many ancient settlements are still visible, with the ones in Kherbet Knisseh, Ain Hercha, or Mhaidseh among the most significant. Rock-cut tombs and necropoleis are carved into cliffs and dolomites in Yanta, Mhaidseh, Kawkaba, Bireh, Tannoura, and many other villages. Jabal el-Cheikh also holds the biggest concentration of Roman-period temples in Lebanon1. Seventeen of them are still visible, with many in good or excellent conditions, such as the ones in Ain Hercha, Hammara, Mdoukha, and Deir el-Aachayer. These temples reveal the particular devotion conjured in antiquity by the formidable presence of Mount Hermon. This sacredness also transpired in monotheistic religions, as the mountain is mentioned in both the Old and NewTestaments and its summit is a site of pilgrimage where the Transfiguration of Christ is believed to have taken place. With this in mind, several villages have safeguarded their historical center. Rachaya al-Wadi is the largest, with dozens of traditional houses organized around alleys, stairways, and a souk, dominated by the “Castle of Independence”. Hasbaya’s historical center is based around the impressive Chebabi fortress and palace. - Vulnerabilities

Like other natural treasures, the region of Jabal el-Cheikh also has some vulnerabilities. Many forests are threatened by desertification because of uncontrolled grazing by goats and sheep, a phenomenon worsened by climate change. Some forests have also been degraded due to excessive firewood and timber collection2. Several archaeological sites have also faced vandalism and damage caused by illegal digs and “treasure hunts”, especially the zones that are most isolated or located along the border with Syria. In Khirbet Knisseh or Haloua, temples have been entirely dismantled in recent years under a total absence of monitoring. The most worrying vulnerability is the lack of land use planning at the municipal and district levels3, which poses a very serious threat to landscapes, especially around urban centers and village cores. This danger has mostly been averted until today, but nothing stands in the way of urban sprawl, in case the area becomes more favorable for future development.

An Insufficient Reserve Law

In December 2020, the Lebanese Parliament approved the establishment of a nature reserve in Mount Hermon. The law was celebrated by many as an achievement for the environment and community. Yet a deeper look into the decision reveals its inability to provide a sustainable, broad-based framework for the protection of the mountain range. The supposed nature reserve covers only one land parcel (No. 5,851), which is owned by the State4. The mountain and the landscapes that deserve protection extend far beyond this single piece of land and comprises areas with multiple land uses and diverse types of land tenures, including private ownerships.

In reality, the integrity of the landscape and its ecological resources are still unprotected. Nature reserves in Lebanon have proven to be partial solutions to environmental dangers. They don’t address the paradigms of land property and fall short of challenging the neoliberal threats. Additionally, the law of Mount Hermon’s nature reserve doesn’t envision an active role for the local community in maintaining and benefiting from the region’s resources. Experience has shown that community engagement in environmental solutions is key to the long-term preservation of ecosystems.

The Regional National Park Model

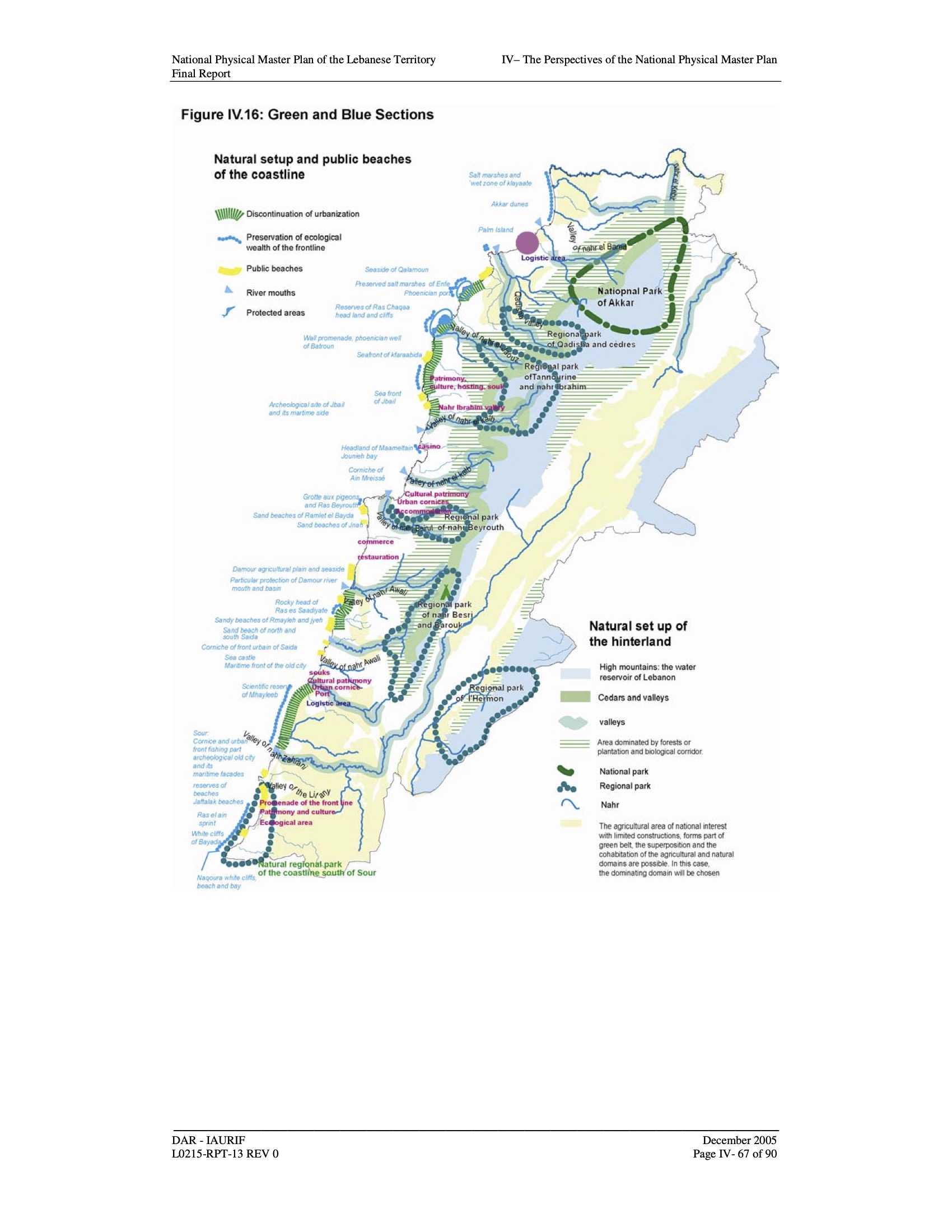

A more strategic approach to the protection of Mount Hermon was adopted by the National Physical Master Plan of the Lebanese Territory (NPMPLT) and approved in 2009. The plan identifies Mount Hermon as a major landscape that contributes substantially to the country’s identity and wellbeing. It recommends establishing the Regional Natural Park (RNP) of Mount Hermon as one of the six major RNPs envisioned for Lebanon [5].

The RNP model is not a binding authority of its own, instead operating as a framework for building consensus and collaboration among those involved from local administrations and community groups, leading to joint projects and master plans that highlight the region’s natural and cultural assets. RNPs are larger than nature reserves, comprising human settlements, forests, rangelands, farmlands, and other landscapes. They establish a nexus between ecological conservation and socio-economic development by encouraging sustainable tourism and environmentally conscious urban development. Unfortunately, the procedural mechanisms that enable the implementation of the RNPs in Lebanon have not been developed yet.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the model of an RNP stands out as the most ideal protection model for the region of Jabal el-Cheikh, given how interlocked human activities, village structures, natural landscapes, and cultural heritage are. It can set the conditions for sustainable development that respects the environment, as well as the needs and aspirations of the local population. However, the Jabal el-Cheikh RNP proposed by the NPMPLT can only take shape if it is supported by an appropriate regulatory framework, masterplans, and a government that puts people’s interests at the center of policy making. Ironically, it has been reported that the approval of the NPMPLT is considered a “mistake” that the current political parties regret, as they were never interested in endorsing a comprehensive land use strategy that transcends sectarian cleavages.

However, some signs remain hopeful. The area is preserved from haphazard development for now, and nothing indicates that this favorable condition could change in the short term. The creation of a natural reserve, though highly insufficient, may be a small step in the right direction, at least in terms of official recognition of the area’s value and exceptionality. Moreover, the ensemble of temples located around Mount Hermon have been placed on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Tentative List, an encouraging move towards the construction of a regional and historical narrative that can drive an interest in the region.

Most importantly, the local population has a high level of attachment to the landscapes that make up the exceptional setting of their daily life. That awareness, paired with a sense of watchfulness over the region’s evolution is vital to its preservation. Such collective involvement must be cultivated and strengthened, as it is the basis for a sustainable future for the region of Jabal el-Cheikh and Lebanon at large.Aliquot, J., & 2006. C. (2009). La Vie religieuse au Liban sous l’Empire Romain (Nouvelle édition ed.). Beyrouth: Institut Français du Proche Orient.

1 Masri, N., & Seoud, J. (n.d.). Sustainable Land Management in the Qaraoun Catchment.

2 Public Works Studio. (2020, November 01). Master-Planning in Lebanon: Manufacturing Landscapes of Inequality. Retrieved from https://english.legal-agenda.com/master-planning-in-lebanon-manufacturing-landscapes-of-inequality/

3 Law for the creation of the natural reserve of Mount Hermon – Law n°202 of 30/12/2020. Retreived from https://mounthermonreserve.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Law-for-the-creation-of-the-natural-reserve-of-Mount-Hermon.pdf

4 National Physical Master Plan of the Lebanese Territory (NPMPLT). (2005, December). Retrieved from https://www.cdr.gov.lb/CDR/media/CDR/StudiesandReports/SDATL/Eng/NPMPLT-Chapt1.PDF

Original Source: https://al-rawiya.com/article-mount-hermon-whats-next-for-lebanons-newest-nature-reserve/

Authors Profiles

Roland Nassour: Roland is an urban researcher, planner and environmental activist. Through his research and work, Roland is interested in making cities more livable, healthy and sustainable. He is the cofounder and coordinator of the Save the Bisri Valley Campaign which aimed to stop the World Bank-funded Bisri dam project, advocating for alternative solutions for water in Lebanon. He also contributed to research projects on public space, urban pollution, and housing rights. Roland is the Community and Advocacy Coordinator at Public Works Studio, currently working on issues related to post-disaster rehabilitation and reconstruction. He holds a Master’s degree in Urban Planning and Policy from the American University of Beirut, and has pursued studies in urban management and climate change at Erasmus University in the Netherlands and in sustainable urban design at Lund University in Sweden.

Antoine Atallah: Antoine is an architect and urbanist. After graduating with a Bachelor in Architecture from the American University of Beirut in 2011, he obtained a degree in urban design from the Ecole d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires. He currently works in Paris on projects of multiple scales, such as territorial planning, design of public spaces, or of new neighborhoods. He is active in the Lebanese civil society, working on diverse heritage, and urban or environmental causes but also on cultural events that highlight the social and cultural dimensions of history, city and landscape. Furthermore, he is the vice president of a non-governmental organization (NGO) called Save Beirut Heritage, member of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) Lebanon and of the Arab Center for Architecture. He intervenes in matters related to coastal privatization, illegal quarrying or with the Beirut Heritage Initiative, a coalition that aims to renovate the historical neighbourhoods damaged by the August 4 Beirut Port explosion.